I’ve been working on this blog post for a while. I keep putting it off because wilderness is a complicated idea near and dear to my heart. Before I begin I feel the need to disclaim that I’m not going to be able to fit all of my thought in one blog post, but that doesn’t mean I should share some of them.

One of the projects I am working on right now is to illustrate a poster for the Nellie-Juan-College Fiord Wilderness Study Area. Last summer I did an artist residency there with the US Forest Service. Some of our preliminary discussions have looked like this: “We’re very open to ideas, but we discussed maybe something where the illustration conveys the feel of the place, or the values of the place…” They said they hoped that wasn’t too broad or open-ended. The truth is it isn’t, and it’s inspiring to have project direction like that. I’ve been having fun thinking about how to create such an illustration.

Sunlight hitting icebergs on stranded on Derickson Spit during low tide.

I love Prince William Sound. It’s a beautiful marine and forest world, part rainforest, part glacier, and part turquoise water. The landscape has gone through natural and human trauma and remains strong, beautiful, and ecologically rich. You can find solitude on a lonesome beach and just around the corner you can find people working hard commercial fishing.

Above: Photos I took as during my residency in Prince William Sound

The water from the Nizina River, which I’m looking at outside my window (under the snow), flows into the Chitina and into the Copper and into Prince William Sound. I haven’t even spent that much time in PWS, but just knowing that it’s there, on the other side of the mountains, makes me feel at peace with the world. That feeling, of knowing something is there, even if it is remote and not visited very often, is part of what is important about wildness in our culture.

Wilderness is a tricky word, because it has a political and a-political definition. The 1964 Wilderness Act recognizes wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain”. Note that “trammel” is a kind of net and means a restriction or impediment to someone’s freedom of action. Despite that thought, it is still defined by a line on the map and rules about how to manage it. It is a kind of beautiful conundrum.

Above: Some of my photos from the Chiricahuas

I’ve worked and volunteered on public lands both in Alaska and in the lower 48 and I know first hand that Wilderness areas are usually managed differently. Machines aren’t allowed to operate in most Wilderness Areas, so I’ve hiked around all summer with a crosscut saw and axe to clear brush in the High Uintas. In Vermont, there are no mileages listed on the trail signs of the Long Trail as it travels through the Breadloaf Wilderness, to make it a more self-directed hiking experience. As Voices of the Wilderness Artist in Residence we spent some time doing trail surveys in the Wilderness Study Area (note the Nellie-Juan College Fiord is managed as wilderness, but it’s actually a WSA, and keeps getting proposed to congress to become Wilderness one day). The Forest Service staff had to decide how to balance the opportunity to do some rare trail maintenance with the importance of maintaining the wilderness character of those trails, which in some cases don’t even really exist.

It’s meaningful to me that our government protects places like the Nellie Juan-College Fiord WSA, that people have conversations about how to manage them, and weather or not to cut a tree down. I acknowledge that most of our public lands have been stolen from other people, but at least they are accessible to many. It’s a privilege to be able to travel through these places. For me, and I think for some others, just knowing that Wilderness exists, even though I may not go there, has intrinsic value.

Being able to visit and recreate in the wilderness is a privilege. This photo was taken on a ridge in the Chiricahua Mountains and in the distance you can see Mexico. Many people travel through this harsh but beautiful landscape with very few supplies and without much choice, just to try to get to a better life.

I’ve gotten the opportunity to participate in several artist residencies on public lands, and I’d like to encourage you to as well. Artists have a unique voice and way of capturing things as complicated as the idea of wilderness. I try in my own way to record my experiences, to inspire people to look closer at their surroundings, and access (even its intellectual access) to untrammeled places.

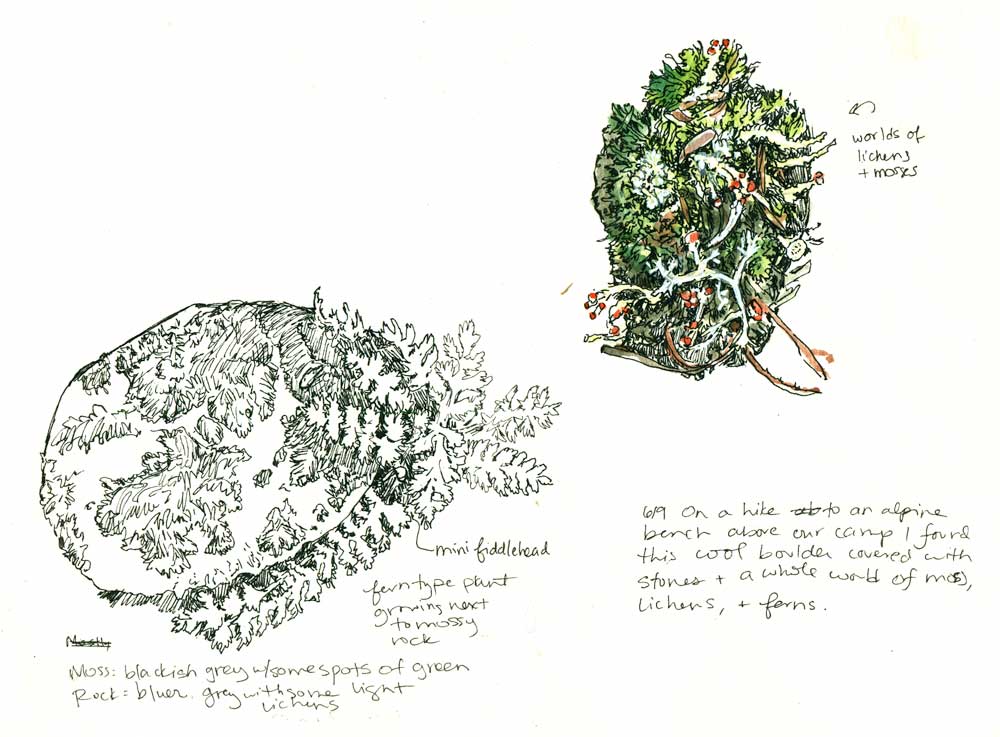

Above are some sketchbook pages from recent artist residencies. Click on them to view a larger version.

I am not sure exactly what my poster illustration will look like, or how it will capture everything that I feel. But like this blog post, I’m happy to put down some of it and make a stab at capturing the beauty of this world, and to share it with you. I thought a bit about how political I wanted to get in this blog post, because right now much of our wilderness is under threat by the US government. I decided I wanted to share some things about why it’s meaningful to me, and hopefully inspire you to have the same conversation with yourself.

There are many artist residency opportunities on public lands, and many of them are operated differently. I particularly encourage artists to take advantage of making art in and about wilderness.

Field sketching on the Noatak River, Gates of the Arctic. Photo by Richard Kahn

Here are a few residency opportunities and programs that I have worked with:

Voices of the Wilderness – Wilderness areas in Alaska run by different public land agencies. Each one is unique but you can apply for many residencies in one application. The deadline to apply is March 1.

Chilkoot Trail – Parks Canada, the National Park Service, and the Yukon Arts Center, and the Skagway Arts Council run this residency together on the international Chilkoot Trail that travels between Alaska and Canada. I am doing this residency in 2018 and really excited about it. Their deadline is February 1st for the following year.

Signal Fire – Is a nonprofit that runs residencies on public lands for small groups of artists and activists. I spent a week backpacking in the Chiricahua Mountains in Arizona last spring. I love the work this organization does! I think their deadline in residencies is January 31st, but their Wide Open Studios application opens Feb. 1st.

Wrangell Mountains Center – Runs residential residencies out of their facilities in McCarthy, AK (where I live and surrounded by the Wrangell-St. Elias National Park). The residencies are self-directed and good for independent people but there are opportunities to meet other scientists and artists working with the WMC (depending on their other programming) and to get out to explore the community of McCarthy and the surrounding areas. Their application is up and closes February 28th.

Gates of the Arctic National Park – Their deadline for applications was December 31, but they offer field-based residencies in an amazing place. I spent ten days floating down the Noatak River in 2011 and it’s an experience I’ll never forget.

Joshua Tree National Park – They have been changing around their AIR program since I did it in 2015, but I'm glad it's open again because it is such an amazing experience to visit and make work in Joshua Tree! The deadline is March 30th.

I didn’t want to get too long winded here, but if something in this post interests you, and you have questions, I would be really happy to talk with you more.

One last thing that I learned about doing these residency programs: they are great to apply to and to participate in, I highly recommend trying. However if the dates don't work or you don't get selected, don't let that stop you from creating your own self-directed residency. I've done that as well and gotten a lot out of it. Get out, enjoy wilderness wherever you find it, make art about it, and share your work (if you want).