In March 2019 I was selected to participate in an artist at sea residency hosted by the Hatfield Marine Science Center and the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology. I spent twelve days onboard the Research Vessel Sikuliaq with a team of researchers from University of Oregon and Oregon State University who are studying zooplankton in the Northern California Current, off the coasts of Oregon and northern California. My cruise was one of four, two winter and two summer, that are funded by the National Science Foundation. After my time at sea I got to spend a week at the Sitka Center for Art and Ecology reflecting on my residency and making work.

I’m putting together a blog series to share my time as artist at sea. I think most people don’t get to see much of the backstory of what it is like to be an artist or a scientist out in the ocean collecting research. For me it was a pretty unique and fun experience so I am happy to take you along. In Part One, I’ll give a little introduction and tour of the research vessel. In parts two-three, I’ll go over two of the main systems used to collect data (ISIIS and MOCNESS) and share some of the art they inspired. In part four, I’ll talk about being a resident at the Sitka Center and some of my plans for future work.

Part 2: ISIIS – Imaging Shadows

Part 3: MOCNESS –Plankton up close

Part 4: Back to Land

ISIIS coming out of the water. Photo by Mark Farley

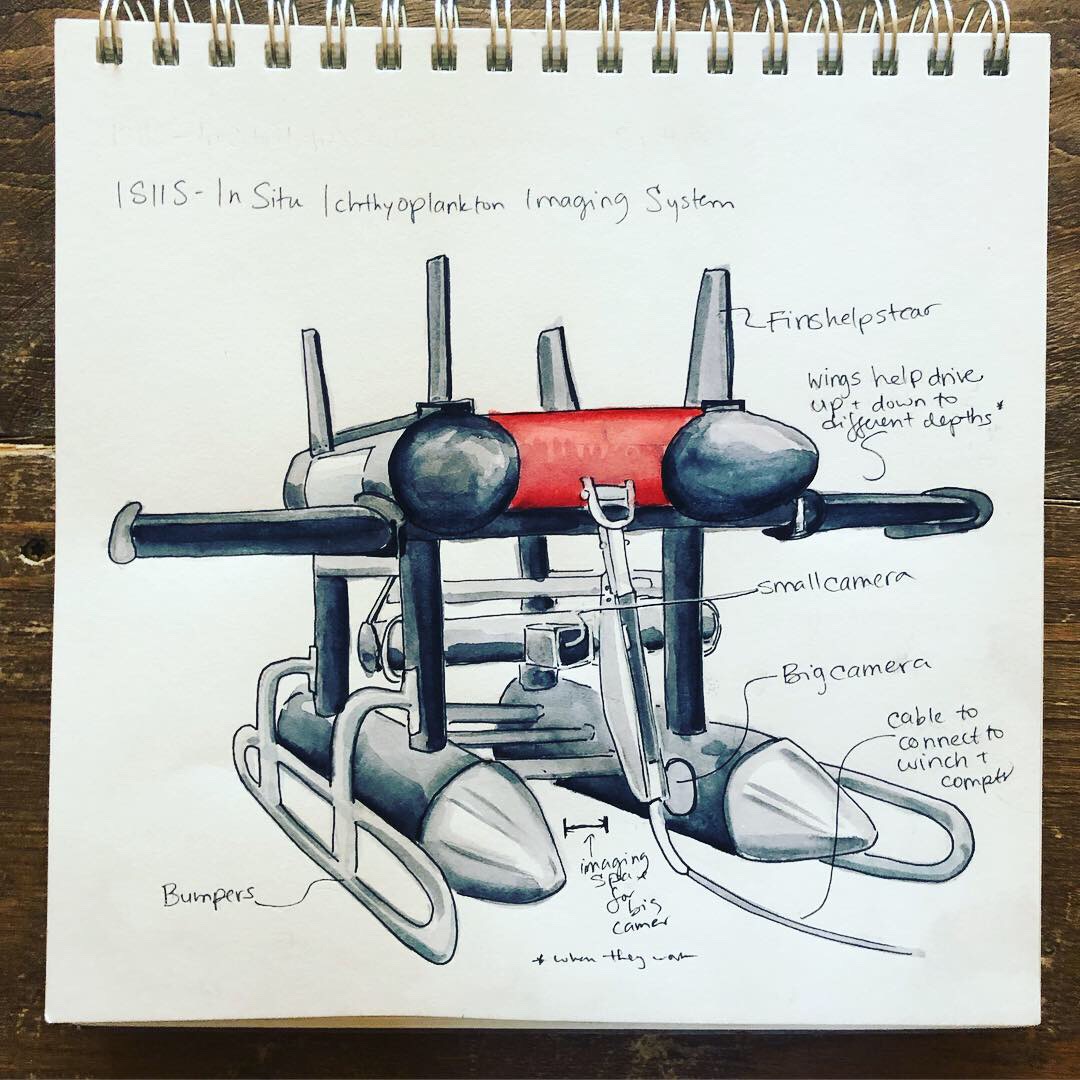

One tool the science team uses to collect information is ISIIS. The In Situ Ichthyoplankton Imaging System (ISIIS) is dragged through the water and collects images from the shadows of organisms that pass through the camera slot. There are two camera areas, one big and one small. Each camera acts like a scanner and shines light through the water to record the shadows of the animals.

Sketch of ISIIS

The project measures two transects off the coast of Newport, Oregon and Trinidad, California. Each transect goes from near shore to the shelf break (where the continental shelf drops away). We sampled each transect twice during the day and twice during the night. That means that we drove ISIIS along the Newport transect four times (two days and nights of sampling) and each transect could take up to 8 hours, because things didn’t always work perfectly. When you measure it up, it is A LOT of imagery, boxes full of hard drives and a giant computer. This is what it looks like watching ISIIS imagery come in live:

It’s a lot of flashing images, but the more you watch it, the better you get at picking things out and recognizing different animals. The scientists keep a binder that they would record sightings in, so we could go back and look at the still images later. I made some recordings too, and a lot of those went like this: “something big”, “something cool”, “giant jellyfish”, “dragon/ sea monster?”, “weird stuff”, “cool siphonophore”, etc.

Above: Series of ISIIS screen shots

After it is collected, the imagery can be run through a computer program to clean it up and to identify types of plankton, such as jellies and larval fish. Especially in conjuncture with the net samples scientists can get a lot of information: what zooplankton are where in the water, in what abundance, under what conditions, who is near who, etc.

ISIIS images can be photoshopped together. Something shredded as it went through. We weren’t sure what it is, but it is beautiful all the same

I would look at the same information and be more focused on finding something big with a lot of detail, like some siphonophore tentacles that take up the whole screen, or a solmissus jellyfish with its tentacles spayed. Gelatinous animals like jellyfish and siponophores are transparent and often have their tentacles out in interesting positions when they go by the ISIIS camera. When we would catch them in the nets they always pull their tentacles in and don’t hold up very well so it is very beautiful to see them in the ISIIS images.

Swordtail Squid swimming

I have been taking these images and creating drawings to make cyanotype prints from, capturing the shadows of organisms in a different way to tell a different story. I’ve been making cyanotypes from drawings for a few years now (you can read about my process in this blog post, and see some of my work making prints of glacial landscapes here). I love the parallel between capturing the shadows of my drawing (by making a cyanotype) and capturing the shadow of an animal (with ISIIS). The blue color works for the maritime environment. I love the technique because I am intrigued by the result which is not quite drawing and not quite photo and captures a ghostly or spiritual quality between worlds.

Above and below: Examples of cyanotypes created from drawings of ISIIS imagery