Five Stories of Water from an Unusual Summer in Alaska:

It was a unique summer in Alaska. The hottest and driest on record, after many other hot and dry, record-breaking summers. On the news I kept hearing about fires and cities in rainforests or otherwise wet climates that were facing drought. Water is always a prominent character in my summer stories. And this year, especially with so much travel around the state was no exception.

Left: Ocean drawing, pen on rice paper/ Right: Stellar and Bering Glaciers, cyanotype from drawing

One: Chitina River

In early July, I flew across the Chitina River to help some friends who were volunteering with the Park Service pack their food and supplies into Bremner (a backcountry historic site). Lynn Ellis, the park pilot said he had never seen the Chitina River so high except maybe once in the 90s. He grew up flying out here, in the Wrangell-St. Elias. The Chitina River, like many of the river is fed by glaciers and floods during hot weather. It appeared to be bank to bank eroding the bluffs on its shores.

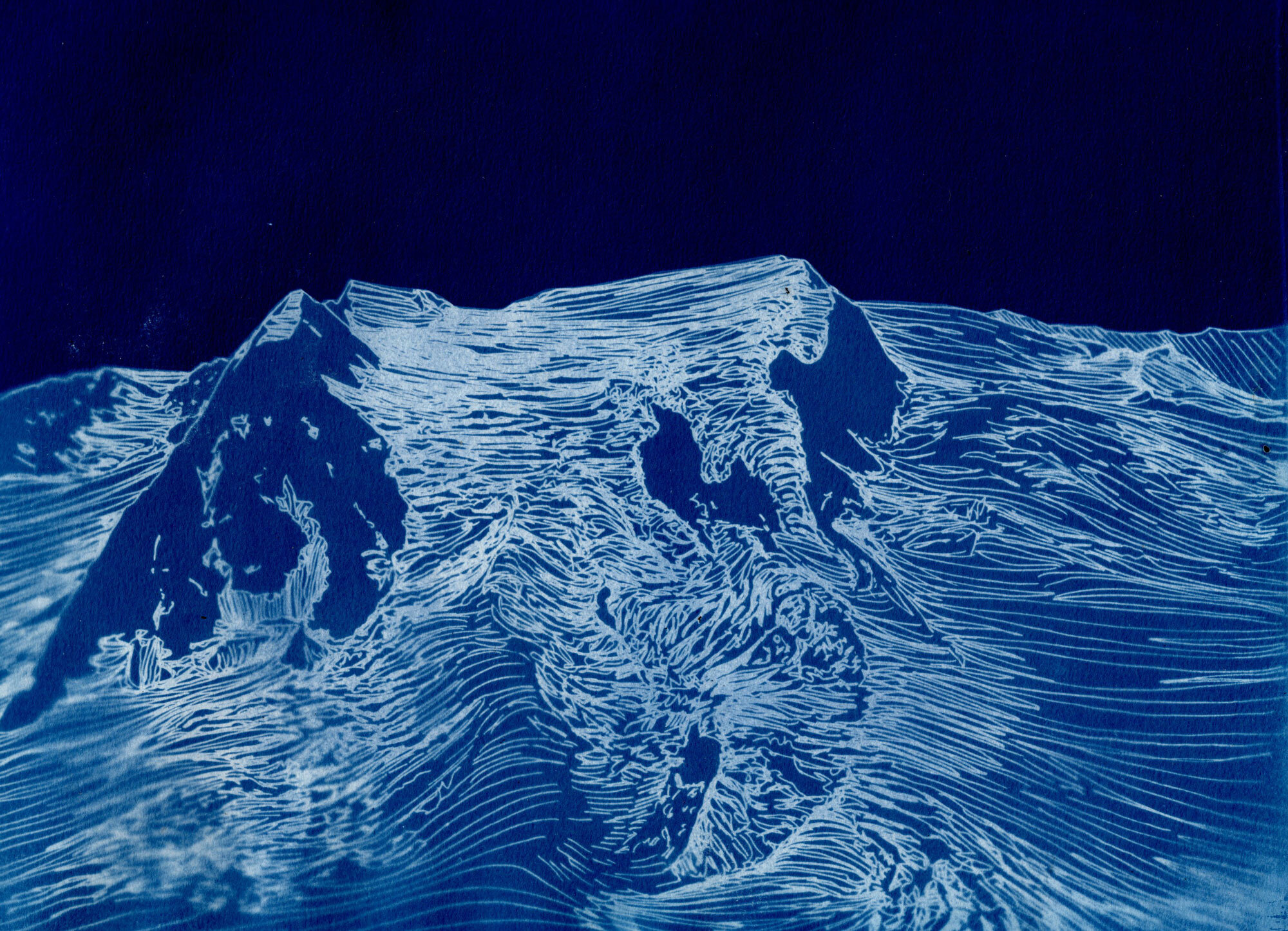

Another Ocean - Cyanotype of drawing, 9 x 12”

Two: Boulder Creek

A week later I guided a backpacking trip to the north side of the Wrangell-St. Elias. We changed our route because the rivers were too high. The airstrip at the Dadina was flooded out and the rivers were too high to cross safely. When I drove to Glennallen the thermometer in my car hit 92 degrees. We were told that a person could not buy ice, a fan, or an air conditioner in the Copper Valley because of this unprecedented heat wave. Maybe not even in the whole state of Alaska. On that trip we crossed the unnamed glacier at the head of Boulder Creek. We couldn’t see Mt. Sanford ten miles away because the smoke from forest fires was so thick. At night we experienced amazing thunderstorms that echoed off the giant mountain and rolled around the glacial valleys. The last night we were there it rained so hard that our cups and bowls were full of two inches of water.

Kayak Island Collection - Pen and watercolor, 8.5 x 11”

Three: Kayak Island

In mid-July we flew from McCarthy to the coast, across swollen glacial rivers, ice fields, piedmont glaciers. All of a sudden, we dropped out of the mountains and blue-sky weather (you could see Mt. Logan about 90 miles away) into the coastal fog, rain, and a lush green landscape. I remember feeling out of place transported from the dry and rocky edge of a glacier to the coastal rainforest. We spent a week hiking around Kayak Island. It is such an amazing and lush landscape. We spent a morning watching whales spout, found seal skeletons and baleen on the beach and in the forest. We watched birds, identified seaweeds, and followed bear tracks as big as dinner plates. However, in such an isolated place, we couldn’t forget our presence on the globe and the impact that humans have on our environment. Mixed in with all of these natural wonders were all types of trash - plastic bottles with labels in every language, glass, fishing floats, every type of buoy, rope, fishing nets, toothpaste, soap, lightbulbs, furniture, laundry baskets, the list goes on. Kayak Island has a unique location where so much that flows through the Gulf of Alaska washes up there. It’s a distant shore strewn with flotsam from humans and nature alike, and sometimes collaboration between the two.

Swirling Moraine - Pen on Duralar Vellum, 9 x 12”

Four: Newhalen River

In early August I went to Nondalton, on the Alaska Peninsula, to teach a youth workshop with the Park Service. We wondered how many students we would have because the salmon were late and many people were still fishing, an important subsistence activity which provides a lot of food for people in the region. We were invited to fish camp one evening. We sat on the shore of the river and talked about the late salmon and the warm weather. People were having a hard time fishing. The water was so warm that all the fish were hiding in the deep, middle of the river and couldn’t be caught using set nets. When fish were caught people had a hard time keeping the flies off them. Usually the fish come sooner before the flies. “It’s a strange summer” elders kept saying. In Bristol Bay I heard people kept finding lots of dead fish and birds. The news kept reporting mass die offs - of salmon, of sea birds, of whales washed ashore.

On the Edge of the Bagley - Cyanotype of drawing, 9 x 12”

Five: Nizina River

Now it’s Fall and I’ve been back home at the Nizina. The Nizina is a glacial fed braided river that fans out to a mile-and-a- half flat flood plain in front of my cabin. I look at it every day and walk on it a couple of days a week. The channels and the flow change every day. Much of the summer, the river runs high, and the main channel comes close to our side of the river. Now it has moved out to the far south bank. Walking the river flats, I see where the channel washed out the road the miners create when they drive up river to Dan Creek. I find debris – five-gallon buckets of hydraulic oil, old rusty barrels, random tools - evidence. I find piles of driftwood, I’ve found salmon eggs like little gems on the rocks where I suppose a bird dropped them. There are bones, bear tracks, moose tracks, rocks of every color.

Goodlata - Cyanotype of drawing, 9 x 12”

The rain came back in October. We had our first frost and our first snows. Things feel somewhat back to normal. The Nizina Glacier has been melting at a record rate, big chunks of it are falling off and the lake at the toe of the glacier (the head of the river) has grown. We used to have a hiking route off the glacier which has changed. The Nizina flows into the Chitina which flows into the Copper and down to the Gulf of Alaska. I drop a leaf here and it could wash up on Kayak Island (though probably it would go West into Prince William Sound instead). The watersheds are what connect us - the glaciers, the rivers, the streams, and the ocean; the rain, snow, and drought that feed them. It hurts to see the water change so much and so dramatically.

Driftwood Figure 17 - Mixed media Digital Collage, 11 x 8.5”